Lance Hill Interview on Prevalent Forms of Racism in post-Katrina United States

Note: Here are a some excerpts from a much longer interview with Dr. Lance Hill, Executive Director of the Southern Institute for Education and Research (Tulane University, New Orleans), which you can read in its entirety here, or listen to in its original form as a radio interview on Democracy Now. This interview was conducted by Brian Denzer for the “Community Gumbo” program on WTUL-FM radio station at Tulane University in New Orleans, and originally aired on January 26, 2008.

*************

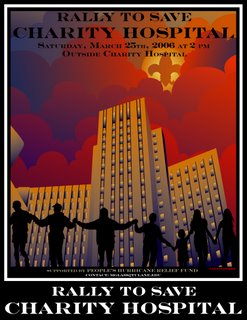

On the Closing of Charity Hospital, and the Lack of Health Care in New Orleans

Lance Hill (LH): The closing of Charity Hospital in New Orleans and the resulting lack of health care for the uninsured is the single greatest obstacle to the return of the black community, given that half of them have lost their healthcare insurance since Katrina.

It’s amazing, because it’s such a huge story, and the New Orleans Times-Picayune won’t talk about it and they never covered any press conferences on the issue for the last two years. They finally covered a recent press conference by advocates for re-opening Charity who had filed a suit to re-open the hospital. It’s an issue unlike the demolition of public housing where you have people in the city who can show up in numbers to protest.

People who need a full-service hospital aren’t here; they’ve moved to Baton Rouge or to Hammond or to out-of-state where there are full-service hospitals for the uninsured. And almost by definition, those who are near death and suffering aren’t the kind of people who can pack and disrupt city council meetings.

I’ve talked to national journalists about this and I’ve said “if you tried to close the only hospital for the uninsured in south central L.A., you couldn’t get away with it. You couldn’t do it in Chicago; you couldn’t do it in Detroit; you couldn’t do it anywhere else....

This policy really causes barbarous suffering and pain for people. There was a horrible story in the paper about a woman who showed up in one of these volunteer neighborhood clinics and half her breast was eaten away, metastasized. She was turned away by a private hospital because they’re only obligated to take you in and stabilize you, not to diagnose and treat you.

But it’s remarkable, just absolutely remarkable, that no national news organization has done a story on this problem....

*****

Post-Katrina Racism in the U.S.

I think one of the ironies of living in post-Katrina New Orleans is that Katrina struck right about the moment when a national consensus was emerging that race no longer mattered. Someone sent me a review of a book, apparently it’s just been published, that argues that race is no longer a determinant factor in political or social, or economic life, and it had nothing to do with Katrina....

The irony is that this national consensus is based on a definition of racism that is forty years old; that one racial group is biologically, intellectually and/or culturally inferior to another group or that racism is a set of practices that denigrates and degrades people and actually inflicts real psychological and physical harm. That in its most extreme form, that racism can result in lynchings, death, and genocide.

But the problem is that we’re using this definition, which is about forty years old, and applying it like a template to America today and then saying we don’t have racism.

But the fact is that racism itself has changed. In the day to day lives of most Americans, the obstacles to progress for African Americans are certainly not nearly as great as they were at the beginning of the Civil Rights movement.

Most African Americans, if they have access to adequate education and resources, can find work and a profession; they can find a decent neighborhood and put their kids in decent schools. The forms of discrimination that exist are subtle and we certainly live in a society where virtually everyone knows that it’s politically self-defeating to openly proclaim your prejudices.

But what Katrina showed, I think, was that we’re far from cured of racism and that in a time of crisis, in which a community is thrown into chaos and people are literally competing for resources for life and survival and trying to keep their families intact, that in the midst of that kind of social and political breakdown and chaos, that deeply embedded racial prejudices reemerged. And they reemerged in very ugly ways.

And it wasn’t just the rescue, but in the recovery phase as well. Two and a half years since the recovery, the tendency of one group to advance itself, to pull itself out of the quagmire of Katrina, at the expense of the other group has really brought out the worst in racial attitudes. All of which culminated in an open “exclusionist movement” to prevent the poor African Americans from coming back to the city....

White people have gotten to the point where they think that, even as a political minority in a city, they have the right to prevent people from returning to their homes where they have lived for generations, in some cases, for centuries, and where their forbearers literally built the city; and that by an accident of nature, poor African American’s have lost their citizenship rights. And that white people, by virtue of having more money, a home that’s above sea level, and the good fortune to have gotten back, have a moral and political right to determine who will return to the city.

To me, this is evidence of a profound problem of racism.

*****

The Need for a New Civil Rights Movement

At some point that needs to be investigated because my sense is that if a similar disaster occurs, be it a terrorist bomb or a natural disaster, to another city with a comparable population of New Orleans, that the same double standard will apply.

I don’t think that there is any question that the first out will be people with resources and money, the first back in will be people with resources and money; and the people who will be charged with planning the future of the city will be the wealthiest and the most powerful. And the temptation to eliminate the problem of poverty by eliminating poor people will be an extremely strong temptation.

If we don’t have a bill of rights for displaced people, and if we don’t anticipate those sorts of problems, we will be in trouble.

That is what I mean when I say there is a need for a new Civil Rights Movement; that we’ve now learned that in these kinds of circumstances that our Constitution and our Bill of Rights and our national principles of treating people fairly and equally don’t apply: we need some sort of guarantees that go beyond our current laws.

*****

The White Exclusionist Movement

[C]ertainly there was in the first year after Katrina a lot of emphasis in the national media on the spirit of volunteerism and people helping one another. But the best kept secret, I think, is that a decision was made very early on by the most powerful elements of this community, and shared across the board among white people who remained uptown, that the future of the city hinged on preventing poor people from coming back: the exclusionist movement.

It is not unusual that in times of collective trauma and crisis that movements emerge that present themselves as visionary--as rebuilding a new society. They almost always construct a role in which there is one source of the problems that the community had experienced before the crisis; and that one source is often a specific group of people. Then that group of people is transformed from victims, in the case of being displaced from their homes, jobs, and loved ones, to becoming perpetrators.

The original victims come to be viewed as obstacles of the realization of the new civic dream.

I actually had someone email me one time because I sent something out about race and disparities and they said “Why can’t we have the city of our dreams?” And I responded, “Because one person’s dream is another person’s nightmare.”

The fundamental issue is that people have a right to return to their homes. Yet there were open pronouncements in the Wall Street Journal by the movers and shakers of this city that they wanted to change the demographics, which was just shorthand for saying they wanted to make the city whiter and more affluent.

If you look at the plans of the two commissions charged with planning the rebuilding of New Orleans, the Bring New Orleans Back Commission and the Louisiana Recovery Authority, both of their initial plans did not allocate a single penny to restore rental properties. Yet 70% of African Americans rented in New Orleans.

When you devise a plan to rebuild a community, and nowhere in the plan have you provided for the kind of housing that the majority of people had before, then you can attribute that to just a blind spot, or an oversight but it doesn’t make any difference to the victims. The outcome is racially and class discriminatory.

*****

I would say that one of the problems early on--some people refer to this as a “conspiracy”-- was the effort to prevent African Americans and poor people from returning.

The proposal to bulldoze the heavily black New Orleans East neighborhood, which, according to the Bring New Orleans Back Commission, the decision would have been made by March 2006—the bulldozing would have been done by that summer of 2006. Gentilly, another major black neighborhood, was supposed to have been destroyed. New Orleans East was to be destroyed; the Ninth Ward was to be destroyed, although the Ninth Ward is actually higher above sea level than predominantly white Lakeview, which was exempted from the demolition plan. And my neighborhood, predominantly black Broadmoor, was to be destroyed.

And early on, some people referred to this as a “conspiracy.” I think that was a misfortunate use of a term, because a conspiracy suggests that this decision was made by a few people without the knowledge or consent of other people. I think this was beyond a conspiracy; it was an open movement. If you were white, everywhere you went—bars, coffeehouses, clubs, the discussion turned to what would be the vision of this new city and how we should not repopulate the poor neighborhoods and should not try to bring back everyone who had lived here before.

This was not a conspiracy; it was a broad movement. It’s a little bit like saying, segregation was a conspiracy. It wasn’t a conspiracy; it was a consensus among white people with the power of law behind it.

*****

National Indifference and the Injustice of Blaming the Victim

I think a far more important question is why have we gone two and a half years with this open movement to deprive poor people of their fundamental rights? Why have we gone two and a half years opening up the Times Picayune and seeing the obituaries filled with hundreds and hundreds and thousands of elderly people, African American mostly, displaced, dying because of neglect, because of stress?

Someone told me they found a homeless quadriplegic under a bush downtown. And two people froze to death right before the big football game and the story was buried in the newspaper.

Why is it that we can have children who spend two months sitting on the floor in a school with no chairs, with no tables, with no books, with no paper, and this is a system run by the state, not by the city, and why can these kinds of unconscionable injustices occur and you cannot name a single white business leader in this community who has spoken out against any of those injustices? Not a single white religious leader of a single denomination has stood up and spoken out against those injustices until Bishop Charles Jenkins did recently.

There are thousands of parents who, in the reorganization of the school system, now have their children in elite charter schools, selective admission charter schools. Their children are perfectly warm, they’re sitting in chairs, they have a nice lunch, they have teachers, they have all of these amenities of modern life, and yet, as this happened just last year, ten blocks away, children are sitting on the floor with no books.

I have a friend who taught at one of the public schools who said they ran out of textbooks six months into the school year, and he spent three months playing basketball with the kids. And for me, the question here is where is the conscience of white New Orleans? Where are those people who understand that silence is confused with consent, and everything we know about the social psychology of harm-doers, of people who commit harm, is they’re encouraged by the silence of bystanders.

You can go across the board with social clubs, civic organizations, business organizations, the chamber of commerce, and there is almost absolute uninterrupted silence in the face of injustice.

At times it’s really been incomprehensible, but I’d have to say that it is predictable is some ways. When people believe that other people are suffering and they don’t do anything about it, they often avoid the guilt by fooling themselves into believing either that the victims aren’t suffering so much.

Eighty percent of displaced people were unemployed a year ago in Texas; they didn’t find the land of milk and honey. Yet all we got from the media were success stories about how displaced people were doing wonderfully. But statistically, that was simply not the case.

The second thing people do to assuage their guilt and prevent them from having to act out of moral obligation is they blame the victim. They think that we live in a just world in which goodness is rewarded and evil is punished; so if these people are without work or without a home, then it’s their own fault. It’s a kind of elaborate rationalization and this rationalizing has resulted in a great deal of suffering and anguish and real physical pain because it has blinded us to the causes of problems.

*****

Brian Denzer (BD): I want to back it up just a little bit. You said in another Gambit Weekly article that hate isn’t the problem—it’s indifference. You said, “I think indifference to the public education of African American youth is a moral crime. The indifference to suffering is the new form of racism.”

And I just want to bring this around to the mission of the Southern Institute in particular, and the ways in which the Southern Institute uses the expressions of hatred throughout history as an example of how to combat indifference, and the ways in which, for example, the Holocaust occurred in large part because of indifference....

One of the keys to that is the power of the bystander. We know from both history and from social science experiments that when one group is harming another group, if people who are unrelated to the perpetrator group or people who are bystanders object to the action, that it inhibits that harming behavior.

So we always emphasize the moral imperative to speak out and act against the persecution and suffering of other people.

That probably explains the many reasons for what I’ve been saying in this interview; that in the last two and a half years since Katrina I have seen very little of this “speaking out” behavior.

What the Southern Institute teaches young people is that to prevent ethnic violence and ethnic conflict and genocide, first and foremost people must act on their own conscience and speak out against the persecution and suffering of other people. And what we know is when they don’t do that, that the suffering and the persecution increases. As we devalue people, that it’s easier to harm people even more.

And we also know that people then will tend to blame the victim for their own conditions. It’s a way of relieving ourselves of our own responsibility and this happens in all kinds of areas.

*****

The Need for Awakening the National Conscience re: Social Justice

BD: Given these intractable problems that you’ve been talking about, healthcare, education, things that have been long-standing, but in particular have come into very sharp relief post-Katrina, in which in many cases are driven by, as you say, a broad movement of racism—are you optimistic or pessimistic going forward that New Orleans can tackle these, what seem like fairly insurmountable problems?

LH: Well, I’m optimistic only because the disparities and the injustices over the last two years are beginning to get national attention.

I know that one million volunteers have come in the last two years and I’ve seen a big change. They initially came in thinking of themselves as humanitarian relief workers, and humanitarian relief really implies that one is going to help people regardless of their needs or income or resources.

Humanitarian relief is almost religiously based in the notion that it does something good for you to help people, rich and poor alike. After Katrina hit, I helped people rich and poor alike; it made no difference, we were just helping people. But as time has gone along, I think people have come back to the city and I think they’ve had the wool pulled over their eyes; that they have not always been helping the communities that needed help the most.

They’ve seen that some neighborhoods have come back and some haven’t. And they’ve asked, “What is preventing these people from coming back?”

That’s when they move toward what they call “social justice” work.

In humanitarian relief work, you’re not trying to change people’s ideas or the systems that produce and reproduce inequality or injustice. But in social justice work, you ask a lot of questions before you come in, and you make sure that the work that you’re doing is work that if you didn’t do it, it wouldn’t get done. And you understand how systems work; that sometimes systems are opaque--it’s not clear where the injustices are; there’s not a “white” and a “colored” sign. But the outcomes can be just as discriminatory.

And so the optimism that I have comes from seeing a growing social movement nationally among young people of conscience who believe that when the old-line white leadership was quoted in the Wall Street Journal saying they wanted a whiter and more affluent city, they got it. They have that city. And if that’s what they set out to do, that’s what certainly occurred.

And I think that the sort of things that Brad Pitt’s doing in the ninth ward, is emblematic that outside the city there’s a perception that people who are inside the city and in positions of power are not attending to those problems and aren’t really determined to solve them.

As an historian, I view this moment very much like Birmingham during the Civil Rights Movement. You come to a point when you have to ask: Do the people in the local community have the moral conscience and the will to correct this injustice? Or is the only solution the awakening of a national conscience and the intervention of a national government?” And usually the answer is both.

*****

The Importance of Admitting Our Failures

I think it’s a very important lesson that we’re far better off letting the nation know what our failures are, and our shortcomings are, because we have a Congress now that is prepared to help and realizes that we don’t have the local resources to accomplish this. And with the new presidential race we may end up with a president who also shares that belief.

There is a sense in this nation, and I’ve talked to people coming into the city and volunteers, that we have our national priorities askew, that we have misplaced national priorities and New Orleans is uniquely positioned because there’s a Congress and there’s a nation out there eager to prove that we are a caring and loving and compassionate country.

And there’s no better place to prove it than in a community in which a natural disaster occurred that was then followed by a human disaster in which the government did not treat its people the way that a great nation should treat its people. And I think Americans have a conscience and they believe that if there’s an injustice, it needs to be remedied.

And so there’s a great benefit for us to make public what the failings are. I think that it only will be through the intervention of the federal government and the resources that it has, that 20 years from now we’ll be a more successful and a better city. So I’m more optimistic now than I was maybe a year ago, but I’m optimistic for reasons quite different than probably most people in the city.

BD: New Orleans is a test care for how we err as a nation, I couldn’t agree more... Dr. Lance Hill, director of the Southern Institute, thank you very much for your time.

Labels: Charity Hospital, Health Care, Katrina, Lance Hill, New Orleans, racism, Southern Institute